I looked down the street I could see the crowd parting the way they always do when the skeletons arrive. Yes; they were coming. But this time they would not have it all their own way. ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

I could tell you it was a hot, dry, dusty day or I could just tell you that it was an average day at the Renaissance Pleasure Faire in Agoura, California in the mid 1980’s.

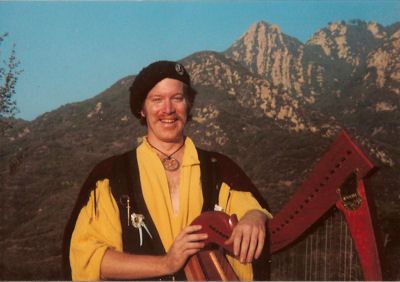

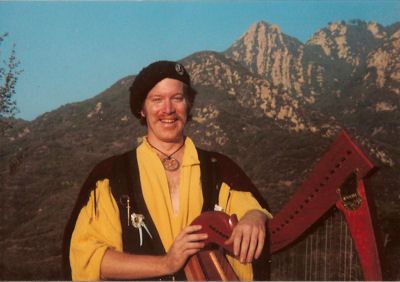

Siamsa - my main harp at the time and the oldest harp I still have - and I were seated by the side of the road, playing Celtic harp tunes for the passers-by and collecting the odd dollar from time to time.

Since Siamsa was being played in the open air she was doing what she usually did, which was to raise a wind. She was feeling good; from time to time I’d have to stop playing when the breeze threatened to uproot the tent of some boothie - sorry, I mean "merchant" - or other. There wasn’t much chance of Siamsa or I being blamed for it, but still. It’s not nice.

I’d already told you it was hot, but from time to time someone would bring me a beer while I played. In the time since I've learned that one can indeed drink a Newcastle without bits of hay floating in it, but to do so is at best an imperfect observance of the tradition.

Harpers do not buy their own beer while they are in the playing-for-strangers space. They must be reliant upon the land and the people or they’re not really in the space. And if you’re not in the space the magic won’t come.

Today Siamsa and I were doing all right. We’d had a visit from a dancer – I know her name, but you won’t. Her friends might read this and so learn things she didn’t choose to tell them.

She was one of many people who would come by for a tune along their business of the day. I’d generally get to play for her when she was on her way to some appointment where she’d meet up with her troupe and her band and they’d either teach people to dance the old country dances, or her troupe would dance some of the dances to keep the year turning; wake up the seeds in the ground – but generally to bring some magic onto people who had no idea. But that’s a large part of it. Catching people unawares with magic.

Today was different. Before she got close my Druid sense told me: she’d had her heart broken. An occupational hazard at Faire, but no less painful for all that. I nodded and glanced at the place on the ground next to my knee where she usually sat to listen and she sat down in her usual spot.

I noodled around on Siamsa’s strings and asked her if she wanted to talk about it. She shook her head, tight-lipped, keeping it all in. She was not going to give that bastard the tribute of a good cry, though I could see she was all full of tears.

Okay, fine. I lightly ran my fingers down Siamsa's soundboard. We got this.

And I played. I played a Burns’ tune, given to me by an old girlfriend: “When My False Love Was True.” I think it was that tune that Ann Heymann had in mind when she once called my playing “fatiguing.”

Heh. “False Love” isn’t fatiguing. “False Love” is a gut-tearing, bleeding memory of betrayed love in G major. When the hands climb up the strings to the upper octaves and begin that hammering, repetitive series of down-arpeggios it’s the cramp of stomach muscles that are sobbing past their limits because they can. Not. Stop.

Without a pause I played “The Tears of Etain.” It’s my variations based upon a Scottish air, “Nighean Donn A’ Chuailein Riomhaich,” if you’re interested. Yes, there's crying in it.

Okay, now to temper it. I played “Carolan’s Farewell to Music” the last song by the greatest of composers for the Celtic harp, in which he put all the love he’d gained from a lifetime of playing for people all over Ireland – people he’d never seen because he was stone blind. The tune he'd written two days before he died.

I took my hands away from the stings for a moment and looked down. Her head was on my knee and my knee was soaked with her tears.

Okay. Good so far. That cry had to happen first. You don't close a wound that's still infected. Now it was time to bring her out of it.

I played plaintive hope, in the form of “Blind Mary.” It was a Carolan tune, written for a friend of his who was also a harper. It was just plain beautiful, and a favorite of a friend of mine who had died not long prior to that.

I played “Carolan’s Quarrel with the Landlady.” The name is deceptive; it’s one of the happiest songs I know.

Her head was up now, and her tears were drying. I shifted the sharping levers out of the key of G and into C and struck up, “Planxty Irwin,” a happy, walking tune about the road rising up to meet you and the wind warm upon your face.

She got to her feet and brushed the dust, and little bits of hay, from her skirts. Her tears were all gone now. She bent down to give me a quick hug, then she was down the street, the little dust-devils dancing attendance on her in her wake.

Siamsa and I went back to our playing and from time to time someone would drop a dollar into the basket. The world was turning as it should.

I felt something, and looked down the street to see. Oh. They were back. Well, they were part of the place too. As I looked down the street I could see the crowd parting the way they always do when the skeletons arrive. Yes; they were coming. But this time they would not have it all their own way.

They’d been part of Faire as long as I had; longer probably. The Danse Macabre - a troop of musicians dressed in bones and rags, playing fiddles and pipes and a marimba – yes, made of bones.

I never learned who they really were; you couldn’t tell under the skull masks and the dripping, flowing shrouds. Besides, who they were wasn’t important. When they dressed like that, and played like that, and danced like that they were the Bones Band and no one else.

There’s plenty of historical background for them, too. After the Black Death swept through Europe, one of the ways people reacted to it all was to dress as skeletons and parade, playing music. Were they getting ready for corpsehood? Or hoping to placate the Angel of Death and be spared? You’ll have to ask them.

I was in no mood to do so. Don’t get me wrong, I had no enmity toward them; far from it. But today I was not in the mood to quiet Siamsa while they went by, the way so many musicians go quiet for the Bones Band parade.

I would not quiet Siamsa. Not today. This once - maybe only this once - the Music of Life was not going to stop for the Music of Death.

So I played. I used to joke when people would ask about the blisters on my fingers when I was playing a day-long busking at the Faire. I said that the blisters had a dampening effect, but when I’d worn down to the bone I got a nice clean release off the strings. Nonsense, of course, but I did get blisters on a long day.

The skeletons were closer; I could tell by the people in the street. And I played “Carolan’s Welcome” and “Carolan’s Receipt for Drinking,” I played the happiest, most alive tunes I could.

I played the wind in the trees on a summer day and the feeling when you know that particular smile is just for you; I played the sails you were waiting for finally appearing at the horizon. I played “Sidhebaeg Sidhemohr” and the smell of fresh beer and new hay; I played the hands pulling you into an up-a-double-and-back in the dance.

They were here. I could see their skeleton feet at the edge of my vision, though my eyes were locked on the strings. I kept playing.

And then a strange thing happened.

Don’t you love that phrase? I use it in most of my storytelling, these days. Like “once upon a time” those words let you know that you’ve left the world you were used to and now you’re in magic country.

A strange thing happened: the Bones Band stopped playing; the fiddlers tucked their fiddles under their humeri, the marimba mallets were lifted from the bones, pipes were pulled away from lipless skulls and in silence they marched on past.

For a moment the Music of Death had stepped aside for the Music of Life.

Siamsa and I kept on playing and if she lifted the tent of some boothie or other I indulged her; she deserved it.

When the Bones Band had passed us, the instruments came out again, the music and the Danse Macabre dansed on. And that’s as it should be. What they play is real, too.

But it isn’t all that’s real, and Siamsa and I belonged on that road, playing the Music of Life, breathing that dust, smelling the beer and hay and sweat and patchouli.

And it was glorious.